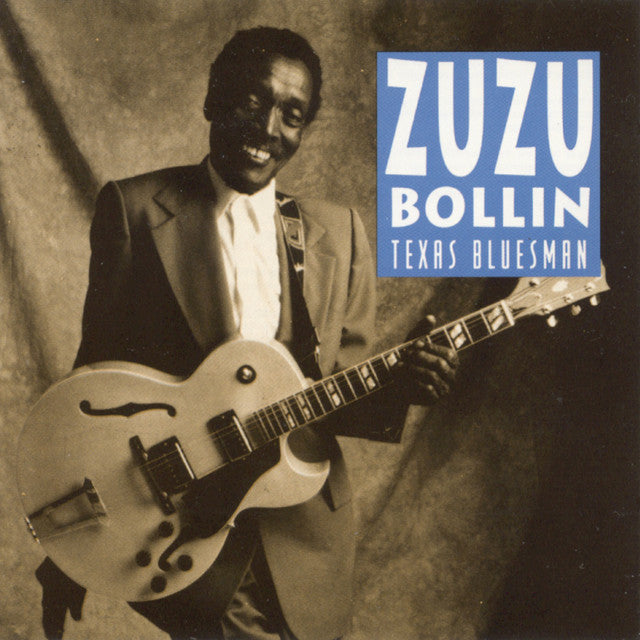

Zuzu Bollin - Record Town Honors a True Hometown Texas Blues Legend

“Why don’t you eat, eat where you slept last night? Get away from my door, else there’s gonna be a fight.” - Zuzu Bollin

Picture of a 78 label of Zuzu Bollin's hit on Torch Records

We are happy to highlight a great, departed local bluesman with close ties to Record Town - Zuzu Bollin. We are including two incredible articles about him previously published by Texas State Historical Association and D Magazine.

The bio from Texas State Historical Association provides a brief but clear picture of the roller coaster life of Zuzu Bollin.

Tim Schuller was a great friend of Record Town and knew the Bruton family well and as you will see, was an accomplished writer. We are honored to feature his article from July 1989 on the great bluesman, Zuzu Bollin.

Zuzu (A. D.) Bollin was born September 5th 1923 in Frisco, Texas. He loved and played the blues. Tim was a local music writer who provided his insight on the Fort Worth and Dallas music scenes for over 35 years before his passing in 2012. As a music lover, Tim wrote for many different publications including Buddy, Guitar Player, Living Blues, and Texas Highways. Along with Chuck Nevitt and Brian “Hash Brown” Calway, Tim founded the Dallas Blues Society in 1987.

Nevitt “rediscovered” Zuzu Bollin and was instrumental in facilitating Zuzu's comeback in the 80's, acting as his manager and producing the acclaimed album, Zuzu Bollin: Texas Bluesman, sponsored by the Dallas Blues Society and released on the Antone's label in 1989.

Record Town is extremely proud to have a number of copies of this rare and historic album available for sale in-store and online.

Sadly, Zuzu’s impressive comeback was cut short by cancer, from which he died on October 19, 1990. But his amazing musical rebirth was nothing short of a miracle.

TEXAS STATE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION BIO - ZUZU BOLLIN

BOLLIN, A. D. [ZUZU] (1923–1990). Blues singer A. D. (Zuzu) Bollin was born in Frisco, Texas, on September 5, 1923. His social security records say he was born in 1923, though most music references give his birth year as 1922. As a boy, Bollin was influenced by two uncles, amateur guitarists, who played the records of Blind Lemon Jefferson and other

early blues musicians.

He moved to Dallas with his mother by the 1930s, served in the navy from 1944 to 1946, and started performing professionally in the postwar years. In 1947 he was living in Denton, where he played in the band of Texan E. X. Brooks. He also performed in bands with such illustrious Texas reedmen as Buster Smith, Booker Ervin, and Adolphus Sneed. During this time he took the nickname "Zuzu" from his favorite brand of ginger cookies called Zu Zu ginger snaps.

In 1949 Bollin formed a group with renowned saxists Leroy Cooper and David "Fathead" Newman. Both of these musicians played on his 1951 recording of one of the true classics of Texas blues, "Why Don't You Eat Where You Slept Last Night?" (flip side "Matchbox Blues"), for the short-lived label Torch. Bollin's voice was deep and strong, and his guitar break was in the jazzy T-Bone Walker. The 1951 piece garnered a bit of regional fame for Bollin, so he figured he was entitled to raise his performance price a bit. Reputedly this irked Dallas nightclub boss Jack Ruby, who used his influence to quash the record.

In the 1950s and early 1960s Bollin traveled around Texas and the United States and toured with various bands, including the band of Joe Morris, which backed such performers as Jackie Wilson. About 1964 he left the music business and went into dry cleaning.

He fell into obscurity that lasted until 1987, when blues enthusiast Chuck Nevitt found him in a poverty-row rooming house near downtown Dallas. Nevitt took Bollin down the comeback trail, acting as his manager and producing the acclaimed LP Zuzu Bollin: Texas Bluesman, sponsored by the Dallas Blues Society and released on the Antone's label in 1989.

Bollin was suddenly ubiquitous in Dallas nightspots. The friendly, personable bluesman sometimes performed with the Juke Jumpers, but his most empathic accompanist was Brian "Hash Brown" Calway.

In 1989 Bollin played at the Chicago Blues Festival and toured Europe, playing at Holland's prestigious Blues Estafette. His impressive comeback was curtailed by cancer, from which he died on October 19,

1990.

Business card from the infamous Jack Ruby who reportedly quashed Zuzu Bollin's record after being angered by Zuzu raising his price after his run of fame.

Record label side A from Zuzu Bollin: Texas Bluesman sponsored by the Dallas Blues Society

ZUZU BOLLIN - MUSIC REBIRTH OF A BLUESMAN

It is folklorically perfect for a bluesman to have been raised next door to a juke joint. In Frisco, Texas, in the Twenties, the local juke joint was the place to gamble, drink moonshine, and dance to a Kirby brand jukebox that held twelve 78 rpm records.

Right next door was the Bollin residence, where a youngster who came to be called “Zuzu” (after a brand of cookie he fancied) could hear the jukebox blare. Born in 1922, the young man grew up to become one of the obscure legends of Texas music. His specialty was “jump” blues, which mixed the emotionality of down-home blues with the citified sound of big-band swing.

Today, most of the great jump musicians are dead. And for a very long time, through the Sixties and Seventies, many fans must have thought that Zuzu Bollin had gone to that great juke joint in the sky.

Indeed, two years ago Bollin was on skid row, with no gigs and no prospects. Since his rediscovery, however, he’s recorded an album, performed with renowned jazz and blues artists, headlined shows in several cities, and been booked for his first appearances in Europe. His return to active performing marks the most significant blues comeback in decades.

“So long, Texas, California here I come. When I get to the arms of my baby, never more shall I roam.”

Zuzu Bollin playing guitar.

On that Frisco jukebox Bollin heard records by Blind Lemon Jefferson, Peetie Wheatstraw, Leroy Carr,

and Doctor Clayton, and he never forgot the power these blues archetypes could pack into a song. But

there were also some big band 78s on the box-numbers by Count Basie, Artie Shaw, Jimmy Lunceford- and even if such music isn’t stereotypically pat in a bluesman’s story, it sure sounded good to Zuzu. He became an ardent music lover, but it would be a while before he considered performing as a profession. In the Navy in the Forties, he did earn the odd dollar strumming hillbilly songs, of all things, in the officer’s club, but he didn’t take it seriously. He planned on pressing clothes for a living. Later, after his discharge, Bollin discovered that a new blues subgenre called jump was popular. Still with no plans for a musical career, he began listening to T-Bone Walker, Wynonie Harris, and Eddie Vinson.

Then, almost overnight, it happened. Bollin moved to Omaha, where he often visited a joint that featured a comic called Rabbit. On a whim Bollin convinced Rabbit, a fellow Texan, to let a homeboy sing one with the band. Bollin let ’em have it with a natural bluesy baritone so impressive he was hired on the spot as the club’s singer. For two months he performed there, following Rabbit. Bollin forgot all about pressing clothes; he was in showbiz!

After the Omaha gig played out, Bollin moved back to Texas, where he played in local bands. It was a giant step up when he joined the mighty Ernie Fields jazz/jump orchestra.

“Why don’t you eat, eat where you slept last night? Get away from my door, else there’s gonna be a fight.”

Zuzu sang for four months with Fields, during which time they entertained at prestigious civilian venues as well as Army camps in Washington, Wyoming, Utah, and Nevada. (“With Ernie Fields you never

played just ’joints,’” asserts Bollin.) After Fields told him to “stick with singin’, boy, ’cause you’ll never be no guitar player,” Bollin, irked, got a guitar of his own and set about honing his skills. He got good enough to hire on as a guitarist on a Percy Mayfield show but quit after touring several states because Mayfield wouldn’t let him sing.

It was in late ’51 that Zuzu made his first record. For the little Torch label, he cut “Why Don’t You Eat Where You Slept Last Night?” with a band that included David (Fathead) Newman and Leroy Cooper. A minor jump classic, “Why Don’t You Eat?” seemed well on the way to becoming a regional hit. Bollin claims, though, that nightclub boss Jack Ruby was angered when Bollin raised his prices after the record’s success. He says Ruby pulled strings to get it off area playlists and jukeboxes. If it happened, the power play doesn’t seem to have done much real damage. Zuzu simply started taking more out-of-town dates, touring again with Ernie Fields, this time for three months.

Musically, Dallas was a happenin’ town in those days. Li’l Son Jackson, Frankie Lee Sims, Buster Smith, Red Calhoun, Red Connors, and other talented locals were on the scene, playing such spots as the Yacht Club, the Empire Room, and the Bob Wills Ranch House. Staying busy, Zuzu played the Savoy Club on Oakland Sundays from 4-8 p.m., and from 8:30-12:30 he played the Sannez Lounge just down the street. A nice break came one night when Li’l Son Jackson got himself double-booked with a Grand Prairie date and an out-of-town gig. Jackson chose to make the out-of-town job, so owner Al Hubbard hired Zuzu to sub. He went over so well that he was booked for two shows a night, two nights a week. Then there were the one-shot promo deals, like a March 1952 opening of Wimpy’s Hamburgers on Singleton, featuring carhops in short skirts, barbecue, and Bollin.

“It was a good scene back then,” recalls the bluesman. “You could get more work than you could really

do.”

The work and the money were good, but life on the blues circuit could be grim. In late 1957, Zuzu hit the road with the Joe Morris outfit. Morris was a Lionel Hampton alum who knew how to do absolutely nothing but blow trumpet, and that’s precisely what doctors had told him not to do.

“Everybody in the band knew Joe was sick” remembers Zuzu. “He’d hemorrhage at the nose, so we’d get ice or ice water and a towel and lean him back, put it on his forehead. This’d stop it. We played our date in L. A., and our next date was in Phoenix, and in a little suburb just outside Phoenix, he hemorrhaged. About four or five in the evening, he started to bleed. Bad. We took him to the bathroom, washed his face, but that didn’t stop it. We had to lay Joe on his stomach because the blood would have strangled him, that’s how bad he was bleeding. We chased the ambulance to the hospital. As fast as they put blood in him, he was hemorrhagin’ it back out.

”Joe Morris died on the road, far from his Alabama home. Zuzu led the band for the rest of the tour. When it was over, he sent Morris’s few possessions back to his widow.

Zuzu’s next tour was with Jimmy Reed, a raging alcoholic who could still slay audiences despite his legendary boozing. The tour broke up after a bad car crackup in New Mexico in which Zuzu almost got killed.

Reed, who had many hits including “Big Boss Man” and “You Don’t Have To Go,” personified the small combo blues sound that, along with the emerging idioms of rock and R&B, usurped the popularity of

jump in the late Fifties. Zuzu kept working but in lesser venues, and he wasn’t as eager to go on the road as he once had been. The death blow to his career came when the Black musician’s union, Local 168, merged with all-white Local 147. Several musicians (Zuzu among them) stress that 168’s books were supposedly in terrible order, and some members did in fact favor the merger (or takeover, as it seems to have been). Still, its deleterious effect was that various Black entertainers of merit could no longer get enough work to stay in the business.

Zuzu Bollin was one. He faded from sight, and no one in the world music community heard a word from him for a quarter century.

“I used to drink and gamble, I used to run around, my burden done got heavy, believe it’s gonna bring me

down.”

Zuzu Bollin with Jimmie Vaughan

In the Seventies, blues audiences burgeoned in Japan, Europe, England, Australia, and America. Old bluesmen were rediscovered and hauled into the limelight. In 1977, Fort Worth’s Juke Jumpers covered “Why Don’t You Eat Where You Slept Last Night?” on Panther City Blues, their debut LP. The 1983 British anthology LP of Texas blues, Down in The Groovy, featured the song and three (the only three) others Bollin recorded. He was alive on the airwaves, but the corporeal Bollin remained unseen.

In 1987, ex-cab driver and blues lover Chuck Nevitt tracked Bollin to a sorry-looking rooming house on Allen Street. He asked the bluesman if he’d like to go to some joints, sit in with the bands. Maybe they could lay the groundwork for a comeback. Hell yes, responded Bollin, who said he was on hard times indeed and if given a chance to sing his way out of them he’d take it, and that was for damn sure. The first place they hit was Fort Worth’s Bluebird, the old-style blues bar with the ambience of a bait store. Zuzu took the stage with the band of U.P. Wilson, a guitarist who counts Zuzu as an influence, and let fly.

For Nevitt, it was an epiphany. Bollin’s voice was more than intact, it was deep, compelling, and incantatory. His enunciation was fine, perfect for the “shouting” style of singing the jump specialists often employed. A few weeks later, after some practice and limbering-up time, Zuzu Bollin was playing exemplary guitar in the delectable T-Bone Walker mode. But his singing was good from the get-go. It is his strongest force and may well be without parallel in the blues world of today.

Bollin’s comeback has been impressive. He’s appeared with old compadres as well as young interpreters, including Roomful of Blues, Buster Smith’s Legendary Revelations, Hash Brown, Anson and the Rockets, David Newman, Branford Marsalis, the Juke Jumpers, and more. He’s done an LP that will be released as a production of the Dallas Blues Society (of which Nevitt is founder). It’s a good record, with accompanists Duke Robillard, Sumter Bruton, Marchel Ivery, and others. Various overseas distributors placed advance orders for the LP-an unusual move, since such orders are usually placed only with established record labels. In fact, the excitement over the return of Bollin may well be stronger overseas than in blues-jaded America. He’s already been signed for a July performance in Belgium, and

in November he’ll perform at a music festival in Utrecht, Holland.

Let’s hope he doesn’t do what some other jazz and blues artists have done and become an expatriate: after a quarter century’s absence, it’s good to have Zuzu Bollin back on the front lines of the Texas music.

Zuzu Bollin with "Hashbrown" and Doyle Bramhall

Picture from recording session of Dallas Blues Society's Zuzu Bollin: Texas Bluesman including Zuzu Bollin, Buster Smith, Doyle Bramhall, Record Town founding family member Sumter Bruton III and Duke Robillard.

Get Your copy from record Town

Check out other Blues Titles On Record Town Records